Paula Hawkins is sitting on my sofa, drinking tea and discussing the best place to hide a body. ‘Wherever I go I always look for places to get rid of people,’ she says, laughing, ‘because, thanks to mobile phones and CCTV, it’s a lot harder now to get away with crimes!’

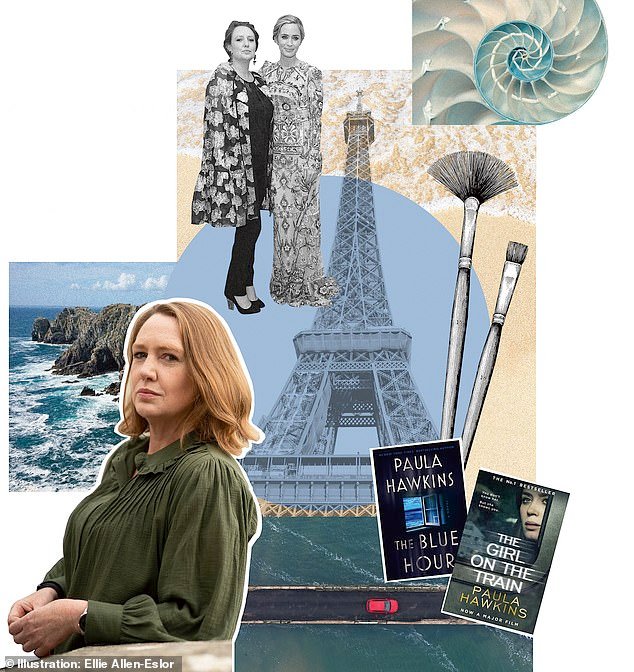

It’s a subject that’s never far from the mind of the 52-year-old author of The Girl on the Train. Published in 2015, the thriller sold 23 million copies worldwide, topped the bestseller lists on both sides of the Atlantic and became the tenth-bestselling hardback since records began. The following year it was made into a film starring Emily Blunt as Rachel Watson, the titular girl who, while staring drunkenly from a train window, thinks she witnesses something sinister.

Hawkins’s genius was to spot something everyone could identify with – who hasn’t stared, bored, out of a train carriage into strangers’ homes that back on to the tracks?

And now she’s done it again with The Blue Hour, a chilling thriller that examines the lengths people will go to in order to belong. It is set on the remote fictional tidal island of Eris, former home of a famous artist, Vanessa, whose unfaithful husband disappeared, and now home to Grace, her faithful friend. The idea was sparked by a beachcombing trip, and finding a shell, a pebble and, most significantly, a bone picked clean. ‘In 2018 I was walking parts of the coast of Brittany where there are tiny tidal islands with just one house on them,’ Hawkins says. ‘I started to wonder: what must it be like to be completely at the mercy of the tide, stuck for six hours twice every day?’

Hawkins lives half of the year in Edinburgh and half in London with her partner of ten years, lawyer Simon Davis. His family owns caravans on the sparsely populated Kintyre peninsula on Scotland’s west coast, where the two often stay. It was no leap to locate Eris there. It is, Hawkins says, ‘extremely fertile ground for fiction’.

Like Rachel in The Girl on the Train, Grace and Vanessa are outsiders. Beautiful Vanessa is in the boys’ club of the art world, fighting to create on her own terms, while Grace, her long-time confidante, is on the edge of Vanessa’s glamorous existence. Feeling like an outsider is a theme Hawkins identifies with. In 1989, when she was 17, her parents moved her and her older brother from Harare, Zimbabwe, to London. ‘It was a culture shock,’ she says. ‘I finished my A-levels at a sixth-form crammer. There were a lot of posh English kids and foreigners, so I made friends with the foreigners. I was quite awkward – shy. I struggled to fit in.’

After A-levels, Hawkins worked in Paris for a year as a chambermaid. When she returned she went to Keble College, Oxford to study philosophy, politics and economics – her father had been an economics professor in Harare. Hawkins was fascinated by young British journalists travelling in Zimbabwe who would visit him to get the lie of the land. ‘They’d lived really dramatic lives; proper foreign correspondents. They were generally unmarried childless women who seemed to be having as much fun as the men.’

She realised she wasn’t cut out to be a foreign correspondent (‘I’m not brave enough’), but an internship on a financial magazine (Central European) led to a consumer-finance journalism job on The Times. There she was approached to write a financial guide for women by literary agent Lizzy Kremer, who is still her agent today. ‘We’ve been together 20 years,’ she says, with a laugh. ‘That’s the longest relationship of my life!’

Hawkins has never been interested in getting married or starting a family. ‘From very early on I knew. Everyone used to say, “You’ll change your mind”, but it has never crossed my mind.’ She continues,

‘If, like me, you’re not religious and you don’t want kids, what is marriage really about?’

Hawkins might be the last person you’d ask to write romance – yet in 2008 she was approached to write a series of romcoms set against the backdrop of the financial crisis. Under the pen name Amy Silver, she put out four novels, beginning with Confessions of a Reluctant Recessionista, which did well. The next two dwindled, the fourth fizzled.

By 2013, Amy Silver was on her uppers, as was Hawkins. ‘I was a financial journalist but I was never good at managing my money,’ she admits. ‘In the early noughties banks were constantly offering interest-free credit cards, and the idea was you could juggle them so you never paid any interest. That was a house of cards. I kept thinking something would just come along but got myself into a mess.’

Yet trying and failing to pen romance had taught Hawkins something important. ‘I couldn’t just write straight romance. I had to have some ghastly trauma to offset it. I blame my mother,’ she says. ‘She grew up on a farm in what was then 1950s Rhodesia. Terrible things did happen. A neighbour was murdered, for instance. Mum had these awful stories and I was fascinated. My imagination cleaved to those darker tales.’

It was such dark imaginings that led her to wonder what gruesome things were happening in the houses she could see from the train. Within weeks of The Girl on the Train’s publication it was clear something had ‘come along’. ‘The Girl on the Train sorted me out [financially]. If it hadn’t, I would have had to sell my house. I was incredibly lucky.’

Hawkins is glad that it took her until she was in her 40s to find her groove. ‘I don’t know how I would have coped if I’d been successful in my 20s. It might have been destabilising. For me it was best to have done the hard yards first.’

More than anything she’s grateful for the opportunities The Girl on the Train has given her. ‘It opened doors,’ she says. ‘Suddenly I was being invited to literary festivals, to judge prizes. It was wonderful. And now I can live comfortably and write books – and very few people can say that.’

Paula Hawkins, no longer an outsider. Who said crime doesn’t pay?

The Blue Hour by Paula Hawkins will be published on Thursday (Doubleday, £22). To order a copy for £18.70 until 20 October, go to mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937. Free UK delivery on orders over £25.

Illustration: Ellie Allen-Eslor.

Getty Images